Don’t Make Me Think Summary: Steve Krug’s Usability Principles

Part I: The Foundation of Common Sense Usability

1.1 Introduction: The “Common Sense” Revolution in Web Usability

Steve Krug’s Don’t Make Me Think, first published in 2000, emerged as a seminal text that fundamentally altered the landscape of web design and human-computer interaction (HCI). Authored by a seasoned usability consultant with over two decades of experience advising high-profile clients such as Apple, Lexus.com, NPR, and the International Monetary Fund, the book distills complex usability theory into a set of actionable, common-sense principles. Its impact has been profound, with sales exceeding 700,000 copies and its adoption as a canonical text in university courses and professional training programs worldwide. The book’s longevity is demonstrated by its multiple editions, most notably the third edition, Don’t Make Me Think, Revisited, which was updated to address the seismic shift toward mobile usability.

The core premise of the book is deceptively simple yet revolutionary in its implications: a good website, software program, or application should allow users to accomplish their intended tasks as easily and directly as possible. The ideal user experience is one that is self-evident, requiring minimal cognitive strain from the user. This philosophy stands in stark contrast to the technology-centric or aesthetic-driven design approaches that were prevalent at the time of its initial publication.

A critical element of the book’s success lies not just in its content but in its form. Krug deliberately designed the book to be short, profusely illustrated, and written in an accessible, witty tone. The stated goal was to create a text that a busy executive could read and absorb on a two-hour airplane flight. This design choice is a meta-application of the book’s own principles. By “omitting needless words” and making complex ideas self-explanatory, Krug crafted a tool of persuasion, not merely a technical manual. The book’s physical design and approachable language were engineered to lower the barrier to entry for usability concepts, allowing them to permeate organizations beyond the design department. This strategic packaging enabled the principles of user-centricity to reach and influence key decision-makers, thereby maximizing its potential to shift organizational culture toward a more thoughtful, evidence-based approach to design.

1.2 Krug’s First Law: The Categorical Imperative of Usability

At the heart of the book is its titular principle, which Krug designates as his “First Law of Usability“: “Don’t make me think!“. He presents this not as a mere guideline but as the ultimate tie-breaker in any design debate—the overriding principle that should govern all decisions. This law is predicated on the concept of cognitive workload, which is the amount of mental effort required to use an interface. Every time a user has to pause to decipher a cryptic icon, wonder if a piece of text is a clickable link, or translate jargon-filled marketing-speak (“happy talk”), their cognitive workload increases.

This mental friction is not benign; it actively depletes what Krug calls the user’s “reservoir of goodwill“. Users arrive at a site with a finite amount of patience and attention. When the interface forces them to solve unnecessary puzzles, it squanders these precious resources, leading to frustration and potential abandonment of the site. The objective, therefore, is to create an experience that is as frictionless as possible.

To achieve this, Krug distinguishes between two levels of clarity. The ideal state for any interface is to be self-evident, meaning a user of average ability and experience can look at it and instantly understand its purpose and how to use it, requiring no thought whatsoever. When this ideal is not achievable due to the complexity of the task, the minimum acceptable standard is to be self-explanatory, where a small amount of thought allows the user to quickly grasp the concept. The principle of “Don’t Make Me Think” is not an argument for “dumbing down” interfaces or removing all intellectual engagement. Rather, it is about the strategic conservation of the user’s finite cognitive resources. It reframes the designer’s primary responsibility from simply building features to actively managing the user’s attention and mental energy, ensuring that those resources are spent on achieving the user’s goal—be it purchasing a product, reading an article, or finding information—rather than on the secondary, frustrating task of deciphering the interface itself.

1.3 Deconstructing User Behavior: The Three Facts of Life

To build usable interfaces, designers must first understand how people actually behave online, which often stands in stark contrast to how designers assume they will behave. Krug crystallizes this reality into three fundamental observations, which he calls the “Facts of Life“.

First, we don’t read pages; we scan them. Users are typically on a mission and motivated by a desire to save time. They approach web pages not like literature to be savored, but like a “billboard going by at 60 miles an hour”. They act like sharks who must keep moving, quickly scanning for keywords, headings, and visual cues that seem relevant to their task, while ignoring large blocks of text.

Second, we don’t make optimal choices; we satisfice. This concept, originally coined by economist Herbert Simon, describes the human tendency to select the first reasonable option encountered, rather than continuing to search for the absolute best one. On the web, this behavior is amplified for several reasons: users are in a hurry, the penalty for guessing wrong is minimal (it costs only a click of the back button), and weighing all available options may not even improve the chances of success on a poorly designed site.

Third, we don’t figure out how things work; we muddle through. The vast majority of users do not read instructions. Instead, they prefer to jump in and try to accomplish their task through trial and error. Once they find a method that works—even if it is inefficient—they tend to stick with it. This behavior is rooted in the fact that for most tasks, a deep understanding of the underlying mechanics is not necessary for success.

These three “Facts of Life” are not isolated quirks but rather interconnected components of a unified theory of user behavior driven by the pursuit of cognitive efficiency. Scanning is a time-saving strategy for information intake. Satisficing is a time-saving strategy for decision-making. Muddling through is a time-saving strategy for learning. The dominant motivation for the average web user is not thoroughness or perfection but speed and the conservation of mental effort. This core psychological reality forms the bedrock upon which all of Krug’s subsequent design principles are built; each piece of advice is a direct and logical response to this fundamental understanding of human behavior online.

Part II: Core Principles for Designing Usable Interfaces

Building on the foundational understanding of user psychology, Don’t Make Me Think outlines a series of concrete, actionable principles for creating interfaces that are intuitive and effective. These principles translate the book’s core philosophy into a practical guide for designers and developers.

2.1 Designing for the Glance: Billboard Design 101

Given that users scan pages rather than reading them, Krug advocates for an approach he calls “Billboard Design 101“. The goal is to create pages that communicate their key messages and functionality effectively at a glance. This is achieved through several core strategies:

- Leveraging Conventions: Web conventions are established patterns that users have come to expect, such as placing the site logo in the top-left corner, primary navigation across the top, and a search box in the top-right. Adhering to these conventions is paramount because it taps into a user’s existing knowledge, drastically reducing the learning curve and allowing them to navigate with minimal conscious thought. Krug strongly cautions against reinventing the wheel unless a new design is demonstrably clearer or adds significant value that justifies a small learning curve.

- Creating Effective Visual Hierarchies: A clear visual hierarchy guides the user’s eye to the most important elements on the page first. This is achieved by making more important elements more prominent through the strategic use of size, color, contrast, and whitespace. Furthermore, things that are logically related should also be visually related—for example, by grouping them together within a defined area—to help users understand the page’s structure instantly.

- Breaking Pages into Clearly Defined Areas: Organizing a page into distinct, visually defined zones (e.g., navigation, main content, sidebar) helps users to quickly parse its contents. This allows them to decide which areas are relevant to their task and which can be safely ignored, a crucial aid for efficient scanning.

- Making Clickable Elements Obvious: A user should never have to devote even a millisecond of thought to whether something is clickable or not. Ambiguity in this area creates unnecessary cognitive friction. Links and buttons must be designed with clear visual cues to signal their interactivity.

- Minimizing Noise: Visual noise refers to any element on the page that is not directly useful for the user’s task. This can include “shouting” (too many elements competing for attention), disorganization, and general clutter. Reducing this noise helps the essential content and functional elements to stand out, making the page easier and faster to comprehend.

These principles of “Billboard Design” work in concert to create a predictable and easily navigable information landscape. By using conventions, clear hierarchies, and well-defined areas, designers provide a cognitive “map” of the page. This map allows the scanning user to orient themselves quickly, identify potential targets, and select a path with minimal conscious effort. This approach directly caters to the “scanning,” “satisficing,” and “muddling” behaviors identified as the fundamental realities of web use.

2.2 The Art of Omission: Eliminating Needless Words and Instructions

A central tenet of Krug’s philosophy is the practice of radical brevity. Because users scan, any text that does not provide direct value is treated as noise that obscures the useful content. This leads to what could be called Krug’s Third Law of Usability: “Get rid of half the words on each page, then get rid of half of what’s left”. This ruthless editing has two primary targets:

-

“Happy Talk Must Die”: “Happy talk” is the introductory, welcoming, or self-congratulatory promotional text that often appears at the top of web pages. It conveys no useful information and is almost universally ignored by users who are on a mission to accomplish a task. Eliminating it reduces the noise level and allows users to get to the substantive content of the page immediately.

-

“Instructions Must Die”: Reflecting the reality that users “muddle through” rather than read instructions, the primary goal should be to design interfaces that are so self-explanatory that instructions become redundant. In the rare cases where instructions are absolutely necessary, they must be brief (the minimum information needed), timely (placed exactly where the user needs them), and unavoidable (formatted to be noticed).

The benefits of this aggressive content reduction are manifold. It lowers the overall noise level of the page, makes the truly useful content more prominent, and shortens pages, allowing users to see more of the screen at a glance without scrolling.

This approach represents a direct challenge to the traditional marketing impulse to fill empty space with persuasive copy. It advances the idea that on the web, superior usability is the most effective form of marketing. A clear, concise page that helps a user achieve their goal quickly and without frustration builds more trust, confidence, and goodwill than a page filled with verbose but ultimately unhelpful “happy talk”. Thus, the act of content reduction is reframed from a simple design choice to a strategic business and marketing decision that directly impacts user perception of the brand.

2.3 Navigating the Void: Street Signs, Breadcrumbs, and Creating a Sense of Place

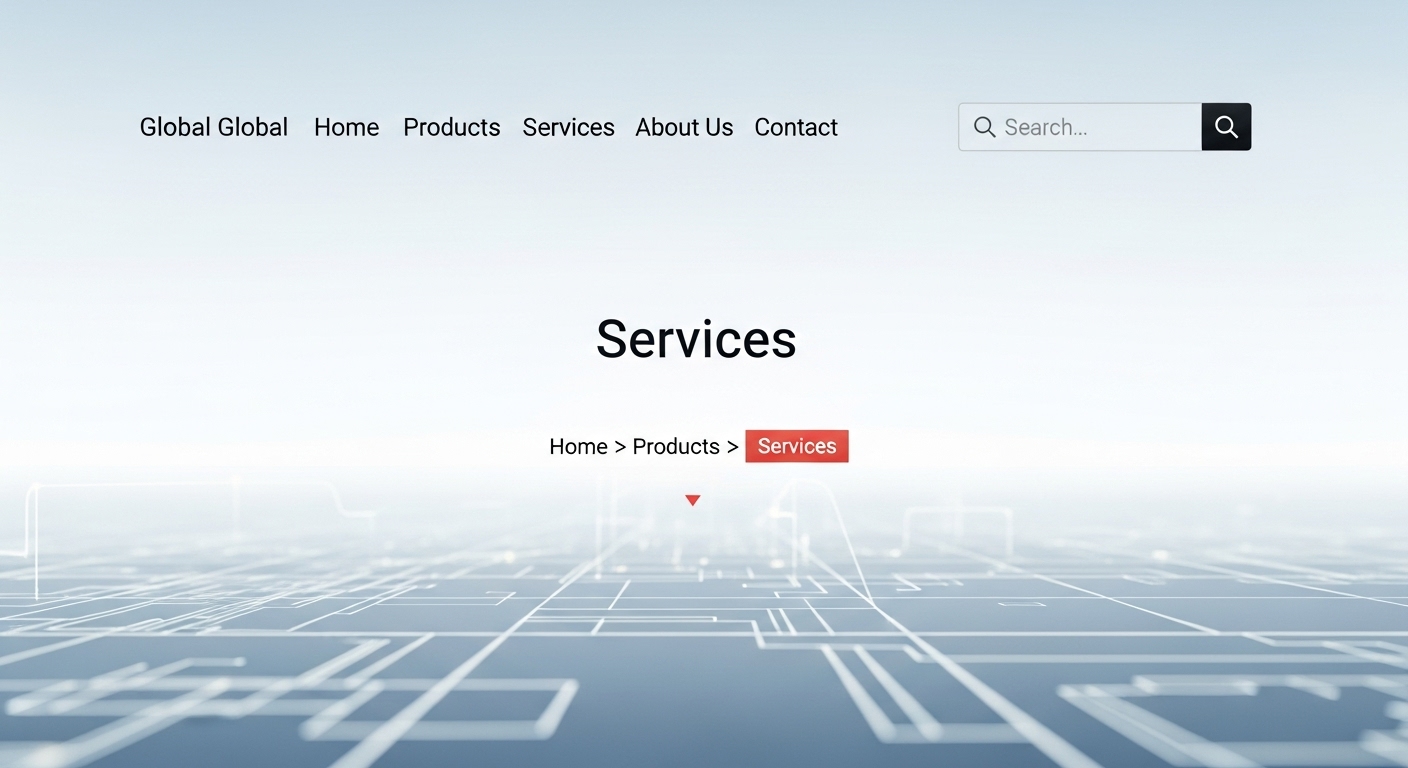

Web navigation presents a unique usability challenge because digital space is inherently abstract. Unlike a physical store, a website offers no natural sense of scale (how big is the site?), direction (is this a step forward or sideways?), or location (where am I in relation to everything else?). Effective navigation design must compensate for this “unbearable lightness of browsing” by providing a clear and consistent set of orientation tools. Key components include:

-

Persistent Navigation: The main site navigation (often a global navigation bar) should be present and consistent on almost every page of the site. This acts as the user’s primary tool for orientation and movement.

-

Page Names: Every page should have a prominent name that clearly communicates its content. Crucially, this name must match the text of the link the user clicked to arrive there. This simple correspondence provides immediate confirmation that the user has made the correct choice and is in the right place.

-

“You Are Here” Indicators: The user’s current location within the site’s hierarchy should be clearly marked in the navigation, for example, by highlighting, bolding, or changing the color of the relevant link.

-

Breadcrumbs: Breadcrumb navigation shows the user the path from the homepage to their current location, clearly illustrating where they are within the site’s structure and allowing for easy, one-click navigation to higher levels of the hierarchy.

-

Search: For users who prefer to search rather than browse, a search box should be a persistent and easily accessible feature on every page.

-

Mindless Clicks: This section introduces Krug’s Second Law of Usability: “It doesn’t matter how many times I have to click, as long as each click is a mindless, unambiguous choice”. This principle prioritizes the quality of a click over the quantity. A user will tolerate a longer sequence of clicks if each step is obvious, confident, and provides a clear “scent of information” that they are on the right path.

These elements work together to address a fundamental psychological need. Web navigation is not merely a feature; it is the very structure that makes a website a coherent and understandable entity.

Its primary function is to provide constant psychological reassurance by answering the user’s implicit questions: “Where am I?” “Where have I been?” and “Where can I go?” A failure in navigation is a catastrophic failure of the entire user experience because it destroys this crucial sense of place, leaving the user feeling lost, frustrated, and lacking control.

2.4 The First Five Seconds: The Big Bang Theory of Homepage Design

The homepage holds a unique and critical position in a site’s usability. It must serve many masters—accommodating site identity, search, content teasers, and various stakeholder priorities—which often results in a design that is a confusing and ineffective compromise. Krug introduces the “Big Bang Theory of Web Design,” which posits that the first few seconds a user spends on a new site are critical. In that brief window, the homepage must successfully orient the user by answering four fundamental questions at a glance:

- What is this? (Site Identity and Mission)

- What can I do here? (Key Site Functionality)

- What do they have here? (Overview of Site Content)

- Why should I be here and not somewhere else? (Value Proposition)

A well-crafted tagline is often one of the most effective tools for answering these questions concisely. If the homepage fails to convey this “big picture” immediately, the user’s entire subsequent journey is jeopardized. They begin exploring without a foundational understanding of the site’s purpose and structure, which makes interpreting every other page more difficult and increases the likelihood of misinterpretation and frustration.

Therefore, the homepage’s primary function is not sales or content delivery, but orientation. It must provide the user with a clear and accurate mental model of the entire site—a cognitive map that they can carry with them as they navigate deeper. A confusing homepage creates a flawed or non-existent mental model, poisoning the rest of the experience by making every subsequent click more difficult and thought-provoking. The homepage is not simply the front door; it is the critical map room for the entire user journey.

Table: Krug’s Core Principles at a Glance

| Principle Type | Principle Name | Core Concept | Key Design Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Krug’s First Law of Usability | Don’t Make Me Think | A web page should be self-evident and obvious, requiring minimal cognitive effort from the user to understand and use. | Eliminate ambiguity. Make buttons, links, and navigation paths clear and predictable. Prioritize clarity over cleverness. |

| Krug’s Second Law of Usability | Mindless, Unambiguous Clicks | The number of clicks to complete a task is less important than the quality of each click. Each step should be a confident, thought-free choice. | Break complex processes into a series of simple, obvious steps. Ensure link text accurately describes its destination (“information scent”). |

| Krug’s Third Law of Usability | Omit Needless Words | Users scan, so excess text is noise. Be ruthless in editing content down to its essential core. | Get rid of half the words, then half of what’s left. Eliminate “happy talk” and unnecessary instructions. Use headings and bullet points. |

| Fact of Life #1 | Users Scan, They Don’t Read | Users are on a mission and will glance at pages to find keywords and triggers rather than reading line-by-line. | Design for scannability. Use strong visual hierarchies, short paragraphs, headings, and bulleted lists to make key information stand out. |

| Fact of Life #2 | Users Satisfice, They Don’t Optimize | Users will choose the first reasonable option they find, not necessarily the best one. | Make the most important and common user paths visually prominent. Don’t overwhelm users with too many choices. |

| Fact of Life #3 | Users Muddle Through, They Don’t Read Instructions | Users prefer to learn by doing and will ignore instructions, trying to figure things out on their own. | Make the interface intuitive and self-explanatory. Rely on established web conventions to reduce the learning curve. |

Part III: Validation and Implementation

Moving from design theory to practical application, Don’t Make Me Think provides a clear methodology for validating design decisions and managing the human dynamics inherent in the product development process.

The focus is on making the process of gathering user feedback as simple, frequent, and effective as possible.

3.1 Democratizing Research: Usability Testing on 10 Cents a Day

Perhaps one of Krug’s most influential contributions is his approach to usability testing, which aims to democratize the practice by making it cheap, simple, and routine. He argues that the primary barriers to testing in most organizations are the perceived cost and complexity, leading teams to skip it altogether. Krug’s “discount” model is a strategic intervention designed to dismantle these barriers.

The methodology is straightforward: test with three to four users for one morning each month. The goal is not statistical validation or finding every single usability problem. Instead, the objective is to identify the most serious, recurring issues—the “low-hanging fruit.” As Krug notes, “You can find more problems in half a day than you can fix in a month”. A typical test session involves a facilitator welcoming the participant, asking a few background questions, conducting a brief tour of the homepage to gather first impressions, and then asking the participant to complete a series of predefined tasks while thinking aloud. After the tasks, the facilitator can probe for more detail before debriefing with the observing team to prioritize fixes.

Krug is careful to distinguish this type of testing from focus groups. Usability testing is about observing user behavior—watching people attempt to use something to accomplish a goal. Focus groups, in contrast, are about gathering user opinions—listening to what people say they like or want. The former provides direct evidence of usability problems, while the latter can be misleading.

The true value of this “10 cents a day” approach extends beyond simply finding bugs. It is a powerful cultural tool. By lowering the barriers to entry, it removes the most common organizational excuses for not talking to users. Its real power lies in forcing a regular, recurring confrontation with user reality. This routine injection of objective user data serves as the “antidote for religious debates” that often plague development teams. Internal arguments about what users want or which design is “better”—what Krug calls the “Farmer and the Cowman” problem—can be resolved not by the loudest opinion, but by direct observation of what works and what does not. This shifts the organizational culture away from subjective speculation and toward evidence-based design.

3.2 Beyond the Interface: Goodwill, Accessibility, and Mobile Considerations

The latter part of the book explores more nuanced aspects of usability that elevate the conversation from pure functionality to the broader user experience.

- The Reservoir of Goodwill: Krug posits that every user arrives at a site with a finite “reservoir of goodwill” or patience. This reservoir is depleted by every frustration, large or small. Things that diminish goodwill include hiding important information (like contact numbers), punishing users for not doing things in a specific way (e.g., requiring a phone number without dashes), asking for unnecessary personal information, or simply having an amateurish-looking site. Conversely, goodwill can be increased by small, thoughtful features that demonstrate respect for the user’s time and effort.

- Accessibility: Krug makes a powerful, humanistic case for web accessibility. He argues that beyond any legal or commercial requirement, making sites accessible is “profoundly the right thing to do” because of the extraordinary, positive impact it can have on the lives of people with disabilities. He also makes the practical point that many of the steps taken to solve general usability problems—such as clear hierarchies, scannable text, and obvious links—inherently improve a site’s accessibility.

- Mobile Usability: The Revisited edition directly confronts the rise of mobile browsing. While the core principles of usability remain unchanged, the constraints of the mobile context—smaller screens, less reliable connections, and distracted users—mean that they must be applied with even greater rigor. On mobile, content must be ruthlessly prioritized, interfaces must be even more self-evident, and technical performance, such as fast load times, becomes critically important. Design must also account for the different interaction model, ensuring that buttons and links are large enough to be easily tapped (i.e., “touch-friendly“).

These concepts of goodwill and accessibility shift the discipline of usability from a purely functional or commercial exercise to an ethical one. The focus is no longer just on efficiency and conversion rates, but on demonstrating respect for the user as a human being. A usable, accessible site that builds goodwill communicates that the organization behind it cares about its audience. This builds a form of deep trust and brand loyalty that flashy aesthetics or aggressive marketing alone cannot achieve. In this framework, usability becomes a proxy for corporate ethics and customer respect, making it a core component of brand identity.

Part IV: Legacy and Critical Perspective

More than two decades after its initial publication, Don’t Make Me Think continues to exert a powerful influence on the fields of web design, user experience, and HCI. Its enduring relevance and its position within the broader UX canon merit a critical examination.

4.1 The Enduring Relevance of “Don’t Make Me Think”

The remarkable longevity of Don’t Make Me Think in a field characterized by rapid technological change can be attributed to one key factor: its principles are rooted in the slow-changing realities of human psychology and cognition, not in the transient technologies of a particular era. As Krug himself notes in the Revisited edition, “usability is about people and how they understand and use things, not about technology… The human brain’s capacity doesn’t change from one year to the next, so the insights from studying human behavior have a very long shelf life“.

Because the book successfully abstracted the core principles of usability away from the specific technical implementations of its time, its framework remains as applicable to a native mobile app or a voice user interface in the 2020s as it was to a desktop website in 2000. The fundamental human behaviors of scanning for efficiency, satisficing to conserve effort, and having a limited cognitive capacity are constants.

As a result, the book is consistently recommended as the essential starting point for anyone entering the UX field and remains a staple of university curricula. It has provided a common language and a shared set of first principles for a generation of designers, developers, and product managers. Its legacy is that of a foundational, “first principles” text. It did not offer a set of temporary web design rules, but rather a durable, technology-agnostic model of user psychology that continues to inform and guide the practice of user-centered design.

4.2 Conclusion: A Foundational Text in the UX Canon and Its Limitations

Don’t Make Me Think has earned its place as an indispensable text in the user experience canon. Its primary contribution was to make the concept of usability accessible to a wide audience. By stripping away academic jargon and focusing on practical, common-sense heuristics, Krug provided a framework that could be immediately understood and applied by designers, developers, marketers, and managers alike. He democratized not only the principles of good design but also the practice of usability testing, empowering teams to gather user feedback without the need for large budgets or specialized labs. In so doing, he fundamentally shaped the user-centric mindset that is now central to modern product development.

However, it is also important to view the book with a nuanced, critical perspective. The very source of the book’s greatest strength—its radical simplicity—is also the source of its primary limitation. It is an introduction, not the final word on usability. Its titular mantra, “Don’t make me think,” is an incredibly powerful heuristic for the vast majority of design situations, particularly in e-commerce and content-driven websites where speed and efficiency are paramount.

Yet, as the broader academic field of Human-Computer Interaction has explored, there are specific contexts where this maxim may not be the most appropriate guidance. For complex tasks involving learning, sensemaking, creative problem-solving, or operating safety-critical systems, interfaces that deliberately prompt users to think more deeply, reflect on their actions, and consider their choices can lead to more meaningful and effective outcomes.

The legacy of Don’t Make Me Think is therefore twofold. It successfully established a universal foundation for usability, creating a baseline of user-centric thinking that has profoundly improved the quality of digital products. At the same time, its success has created such a powerful and pervasive meme that it can sometimes overshadow more advanced conversations about the contexts in which “making users think” might be a valid and even desirable design goal. The book is the brilliant and essential first chapter in the study of usability. The mark of a mature design practitioner is not only to have mastered its lessons but also to have learned when and how to move beyond them.